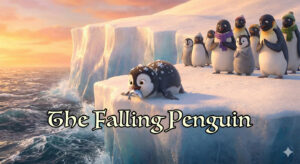

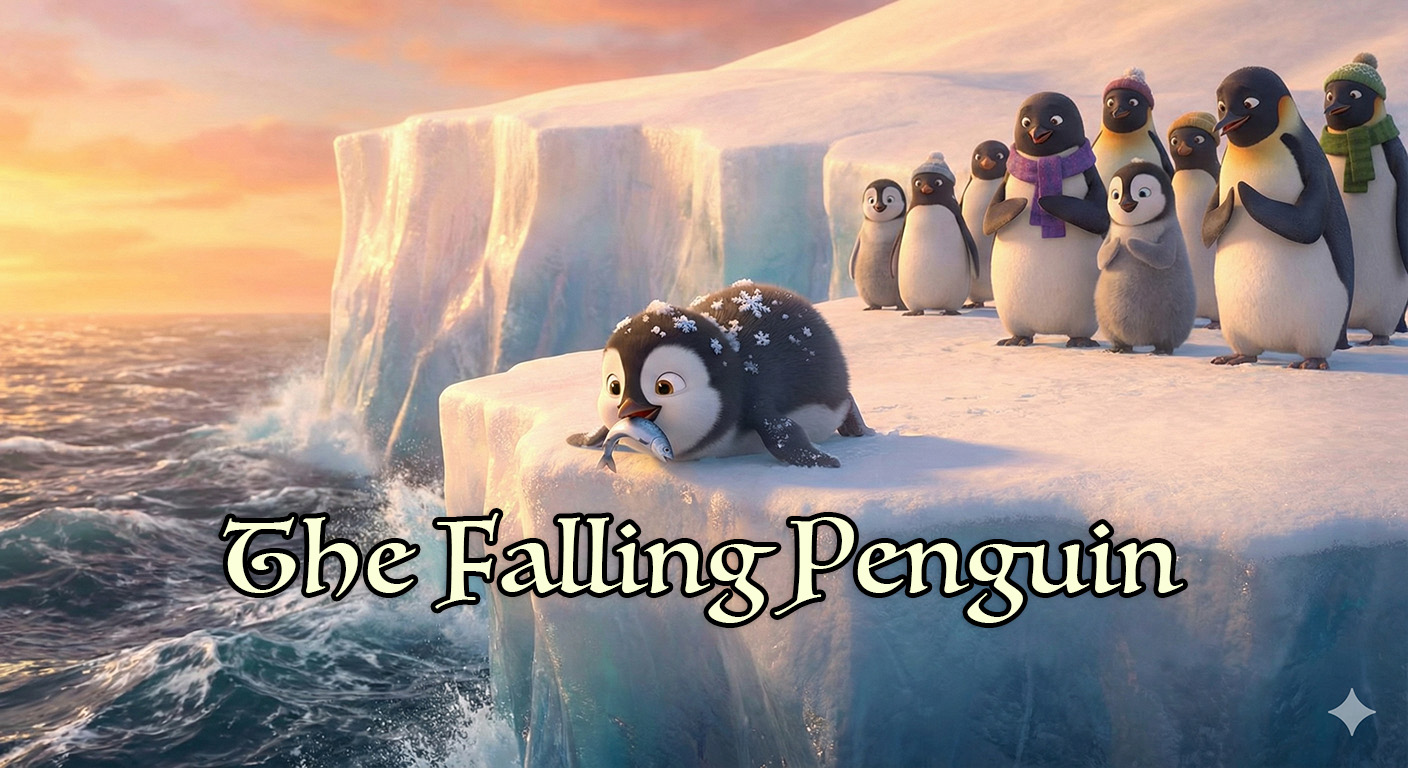

The Falling Penguin

A story about Strengh

On an ice shelf at the edge of the world, where the sky met the sea in shades of silver and blue, lived a colony of penguins. They were a proud bunch—sleek divers, graceful waddlers, masters of the frozen edge where land surrendered to ocean.

And among them was Pebble, the smallest penguin anyone had ever seen, and also the clumsiest.

Pebble fell. A lot.

She fell waddling to the water. She fell climbing back onto the ice. She fell standing completely still when a gust of wind caught her by surprise. The other penguins had stopped counting.

“Weakling,” some of them muttered as she tumbled past. “Clumsy little thing,” others whispered.

One day, Frost—the colony’s best fisherman—watched Pebble fall three times in the span of a single waddle. His expression was stern. “You need to grow stronger, Pebble. Learn to stand properly. You can’t keep falling like this.”

Pebble’s face burned with shame. She turned to walk away and immediately stumbled over her own feet, landing beak-first in the snow. Behind her, she heard the snickers.

The winter that year was the harshest anyone could remember. The storms came early and stayed late. The ice shifted and cracked. The fishing grounds moved farther and farther from shore.

One morning, the colony gathered at the edge of the ice shelf. The water below churned with fish—more fish than they’d seen in weeks. But the jump was higher than usual, the water rougher, and the climb back up would be steep and slippery.

Frost went first. His dive was flawless. He surfaced with a fish, swam to the ice wall, and launched himself up. He made it to the top, but the moment his wet feet touched the icy surface, they shot out from under him. Frost fell hard on his back.

He lay there, stunned. He’d never fallen like that before. Didn’t know how it felt. Didn’t know what to do with the shock of it, the embarrassment, the way his confidence cracked like thin ice.

He stayed on the ice, but he didn’t get up to try again.

One by one, the other penguins tried. One by one, they fell on the slippery ice—some on their bellies, some on their backs, some tumbling sideways. And one by one, they gave up. The fall had surprised them. Hurt them. Made them afraid.

But Pebble?

Pebble jumped, caught a fish, climbed, and fell flat on her face. She got up. Jumped again, caught another fish, climbed, and fell on her side. She got up. Jumped again, fell backward. Got up. Jumped again, slipped, rolled, and ended up with her feet in the air.

“Why do you keep trying?” called Frost from the water, where he’d been watching. “You fall every single time!”

Pebble stood up, shook herself off, and looked at him with her head tilted. “I fall every single time anyway,” she said. “At least now there’s fish involved.”

She jumped again.

By sunset, Pebble had caught more fish than anyone. She shared her catch with the colony, and everyone ate well that night.

From that day on, nobody mocked Pebble for falling anymore. Frost would nod respectfully when she tumbled past. The elders would smile knowingly when she picked herself up for the hundredth time.

And something interesting began to happen.

The younger penguins started falling on purpose—practicing their tumbles, learning to roll, teaching themselves to bounce back up. Then some of the older ones joined in. Soon, on quiet afternoons, you could see penguins of all ages flopping onto the ice, experimenting with different ways to fall and rise, fall and rise.

They never said they were copying Pebble. They didn’t need to.

Pebble still fell more than anyone else. But now when she got back up, she wasn’t alone anymore.

Here are more stories for you to enjoy: