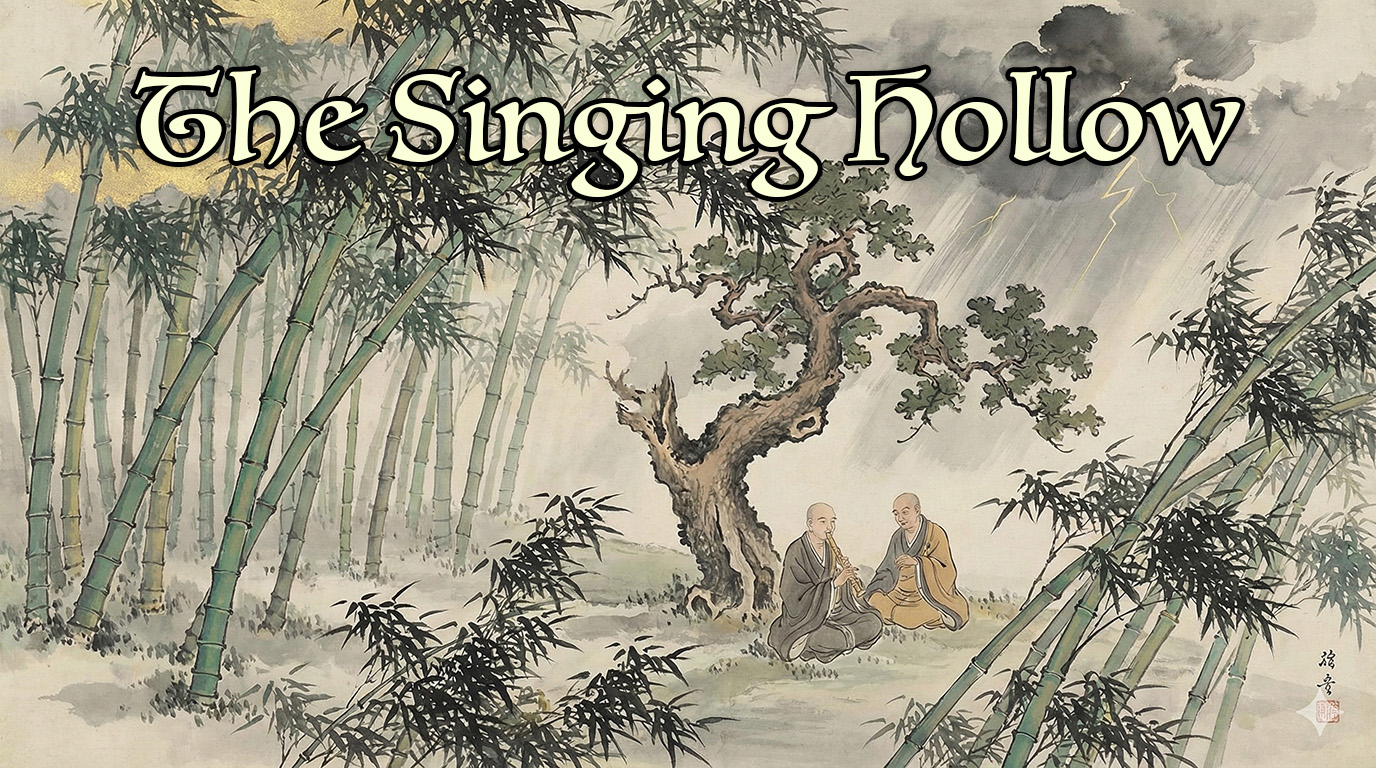

The Singing Hollow

A story about Confidence

There was once a young musician who had studied the flute for seven years beneath a master whose melodies could make rain fall upward. The student’s technique was flawless—his fingers knew every position, his breath was measured and true—yet when he played, the sound was like water trying to remember how to flow. And when others gathered to listen, his hands would tremble as though possessed, and the notes would scatter like frightened birds.

“I have learned everything,” the student said to his master, “yet I possess nothing. My music is a shell with no creature living inside it.”

The master, whose name was Tenzin and whose eyes were the color of smoke, did not answer with words. Instead, he gestured for the student to follow him into the mountains.

They walked for three days through forests where the trees whispered in languages older than men, until they arrived at a hidden valley where a grove of bamboo grew. But this was no ordinary bamboo—each stalk was perfectly hollow, and when the wind moved through the valley, the bamboo sang. Not the creaking of ordinary plants, but true songs—wordless melodies that seemed to contain all the grief and joy that had ever existed.

A storm was gathering in the east, its clouds the color of old bruises. Tenzin led his student to the edge of the grove where an ancient oak stood, and sat beneath its massive canopy.

The student settled beside him, feeling the oak’s thick trunk at his back. For the first time in days, he felt safe—protected by this great pillar of strength, sheltered beneath its unwavering branches.

“Watch,” Tenzin said.

The storm arrived like an army. Wind struck the valley with such force that the student was thrown to his knees. He looked up, certain the bamboo would be destroyed—these tall, thin stalks with their delicate walls, surely they would snap.

But they did not snap. Instead, they bent, some so low their tops nearly touched the earth, yet their roots held fast. And as they bent, they sang—a great chorus of hollow stalks, each one a flute played by the storm itself.

The oak did not bend. It stood against the wind as though defying the storm to move it.

Then came a tremendous gust. There was a sound like the world breaking, and one of the oak’s great branches tore away and crashed beside them.

When the storm had passed, Tenzin spoke.

“The oak believes in its own solidity. It has grown thick and full of itself. But pride is not roots—it only looks like strength. When the storm tests it, there is no space inside for the wind to pass through. And so it breaks.”

He placed his hand on the nearest bamboo stalk. Despite the violence it had endured, not a single one had cracked.

“The bamboo is hollow. Because it is empty, it can be filled—with wind, with song, with whatever comes. It does not resist the storm or try to prove itself. It knows the storm will pass, but the roots go down forever into the earth.”

The student touched the bamboo, feeling how thin the walls were, how impossibly fragile it seemed.

“But Master, if I make myself hollow, won’t I disappear entirely?”

Tenzin smiled. “You are already hollow. Every living thing is. The question is what fills the hollow space—whether it is filled with your fear, your need to be seen as strong, your desperate grasping at certainty… or whether it is empty and clear, like these bamboo, waiting to be played by something larger than yourself.”

He drew a flute from his robes—one carved from the bamboo of this very grove—and played a single note. The sound was unlike anything the student had ever heard. It was not Tenzin playing the flute, but the flute remembering what it had sung when it stood in the grove, and Tenzin was merely the space through which that memory could flow.

When the note faded, Tenzin handed the flute to his student.

“Your hands shake because you believe you are the one making the music. But you are not the music. You are the hollow through which it passes. And the hollow cannot fail—it can only be clear or clouded, open or closed.”

The student raised the flute to his lips with trembling hands. But this time, instead of fighting the trembling, he simply noticed it. He became aware of the hollow space inside the instrument, and the hollow space inside himself—the empty place that had always frightened him.

He blew a single note.

It was not a perfect note. It wavered and cracked slightly. But it was true in a way his perfect notes had never been, because it came from the hollow, not from his fear.

“When you play from that place,” Tenzin said softly, “from the hollow that knows it cannot break because it is already empty—then your hands can shake all they wish. The music will still be true.”

The student looked at the bamboo still swaying gently in the aftermath of wind. He understood now: confidence was not the absence of fear, but the presence of that deep, rooted emptiness — the hollow that could bend without breaking, the void that could be filled with song, a nothing that even fear cannot touch.

Here are more stories for you to enjoy: